by Paul R. Spitzzeri

A particularly notable and interesting section of the Stanford Research Institute’s report on the City of Industry from incorporation in 1957 to 1970 is its discussion of industrial land use in the city and more broadly in the region. From that wider context, the authors noted that “the past and future development of City of Industry must be considered in relation to the past and future development of Southern California.”

It was general regional growth that would determine land prices and which industrial types would come to the city. So, the writers examined regional trends and patterns in industrial land uses, saturation in this aspect, and pricing trends as “a framework for estimating possible future trends in industrial land utilization and prices.”

As stated, the post-World War II era included a transformation in the use of industrial land in southern California and studies from the state’s Department of Water Resources during the 1950s were considered “the most comprehensive inventories of this type ever conducted in the United States.” Using this data, the authors compiled information for Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside and San Bernardino counties as quantified in two tables.

For Los Angeles County, industrial land expanded from under 20,000 acres to nearly 28,000 in ten years, with the number of employees growing from just below a half million to 870,000. Estimates for the other three counties for 1960 from material gathered by the state and the Stanford institute were that acreage zoned for industry was about 23,600 acres in Orange, 5,555 in Riverside, and nearly 35,000 in San Bernardino counties. Actual utilized acres, however, was 1,700 in the first, 510 in the second, and 915 in the third. Total employment, respectively, was over 50,000, over 15,000, and about 27,500.

The idea of saturation was to determine which areas regionally were built out or had growth room for industrial uses. The state water resources inventory data was broken down into 35 districts in Los Angeles County, with City of Industry as part of #26, denoted as “Puente Hills.” The institute excluded four districts because of their isolation, these including Santa Catalina Island and the northern reaches of the county in the deserts north of the San Gabriel Mountains.

A lengthy table looked at industrial land in each district by those that were zoned and those in actual use. The report noted that although there was tremendous regional growth after the war, “there is still considerable room for industrial growth,” with a little under 40% of all zoned industrial land in use. In the Puente Hills district, the industrial area was almost completely (93-95%) within City of Industry, and less than 10% was being utilized, maing it one of the least saturated areas in the county. Close to 6,000 acres were not used and only the area around Los Angeles Harbor had more room for industrial growth.

By mid-1963, City of Industry had about 6,250 acres within its boundaries, though about 5,300 acres was left after accounting for streets, flood control channels, railroad lines and others, and 94% of it was zoned for industrial uses. while 5% was set aside for commercial development, and 1% for “industrial-public building.” The commercial zoning included California Country Club on the west end of the city, while the “industrial-public building” likely meant the civic center and, perhaps, the Homestead site, which was acquired by the city betwee 1963 and 1975.

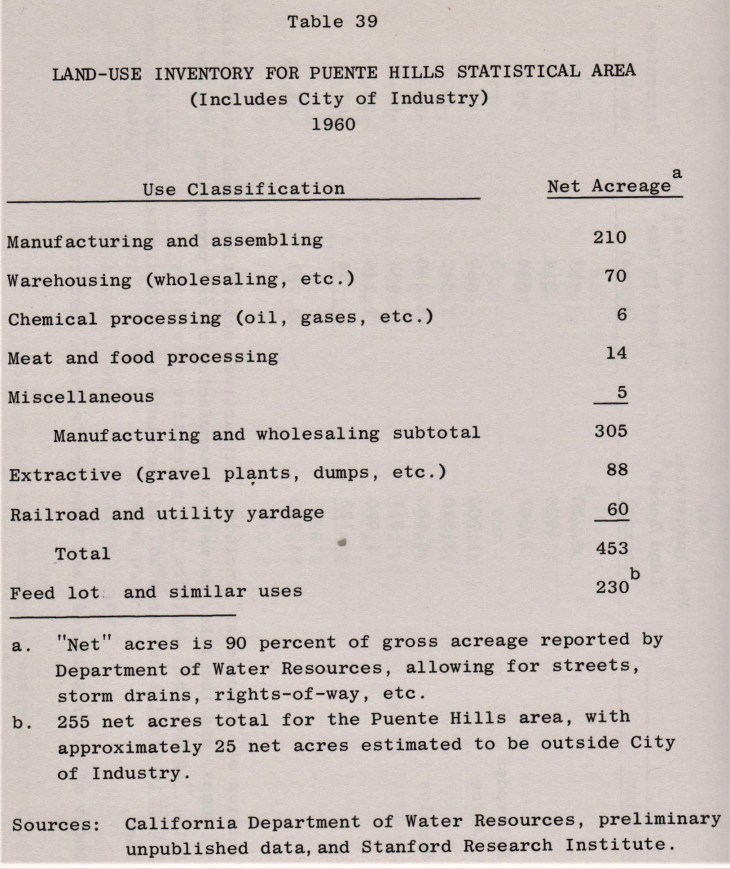

Of that net acreage in 1960 in the Puente Hills district (5,270 of 6,220 in Industry) only 450 was in use, just 7.4% of the total. Nearly half was in manufacturing and assembling, comprising 220 acres, with 70 acres in warehousing and 25 in various uses (chemicals, food processing and miscellaneous.) Another 150 acres comprised railroad and utilities and extractive (meaning gravel plants, dumps and others.) About 230 acres were denoted as “feed lot and similar uses,” presumably the Stafford Mill and ranching areas. Since 1960, though, there had been significant growth in the city, so that about 710 acres were in use by mid-1963, a major increase in three years.

With respect to land prices, it was observed that there were many factors affecting this, including labor supply, wage levels, transportation costs, taxes, amenities for nearby residential areas from where laborers came, and others. The authors, however, also noted the relevance of mass psychology “with resulting periods of undue optimism and pessimism.” So, the economic of land was not at a stage where accuracy could be found in predicting trends.

Pricing, however, was complicated, beyond sale prices (which could be below or above market value), and could be difficult because of the variable factors involved in a given property (size, access to transportation, cost of utilities, and so on.) What the authors did is rely on pricing information given by realtors specializing in industrial properties, though it was acknowledged that faulty memories could skew the information obtained, unless realtors and firms maintained good records of past sales.

An accompanying map showed fourteen areas in the region surveyed for industrial land pricing from Santa Ana to Canoga Park and from San Bernardino to El Segundo, while a chart showed the trending of those prices for the given areas. The result was that land appreciated at rates ranging from 5 to 16 percent annually, with the lower amounts found in Burbank and nearby areas and the highest in two Orange County areas (near Santa Ana and in the Placentia-Anaheim section.) Prices per acre were as high as $80-85,000 in El Segundo and Vernon to $5-6,000 in the Inland Empire region.

As to City of Industry, it was found “the price of land . . . has appreciated solidly but not spectacularly since 1956,” and that the further west (and in closer proximity to Los Angeles and the San Bernardino Freeway), the higher the value. In fact, property at the eastern end of the city before the opening of the Pomona and Orange freeways (State Routes 60 and 57, respectively) were “probably priced as low as any land in Los Angeles County located south of the San Gabriel Mountains.”

Industry was compared to the City of Commerce, which was considered more centrally located, with better access by freeway to Los Angeles and the harbor and other areas of the greater basin. Low property tax rates, good schools in nearby cities such as Montebello and Downey, and sales and other tax revenues were sufficient to handle most city expenses. In Orange County, a huge growth in population meant manufacturing employment more than tripled, while Los Angeles County only saw a 12% increase. Land prices rose accordingly in Orange County industrial zones, as noted above.

The slow growth in Burbank was said to be due to anemic growth in aircraft operations, while the Inland Empire regions were adding large areas of industrially zoned land “even in the absence of significant industrial demand.” It was even suggested by realtors that much of this property would be converted to residential use, though a major industrial push to that area would later come.

Returning to the City of Industry, some realtors stated that it “is in a ‘backwater’ area, not easily accessible from many areas of Los Angeles and Orange counties.” At the west end, conditions were better, but the eastern portions of the city suffered from inadequate transportation routes. A parenthetical note, however, indicated that, by 1970, “most of this relative isolation will be broken in two to six years with completion of major portions of the Pomona Freeway to Los Angeles and the San Gabriel River and Brea Canyon [Orange] freeways to the coastal plain.”

There were also issues with streets and roads within the city as well as with railroad grade crossings; with unattractive surroundings, including junk yards, pizza parlors (!), and others—these causing some firms to think twice about relocating to Industry; and “considerable evidence that the City has acquired a reputation for political controversy, and this has not encouraged industrial development.” Yet, the authors cautioned that “it is not within the scope of this research to prove or disprove the validity of the opinions which were found to exist, but merely to report them and assess their significance.”

The next part of this series moves to “Projected Industrial and Economic Growth of City of Industry,.”