by Paul R. Spitzzeri

This concluding entry in an in-depth look at a key document of the early history of the City of Industry starts with an analysis of problems and possible solutions with special purpose industrial cities. One was a perception of imbalance, with the response being a policy of annexing land that creates a “balanced community,” with residential development and industrial uses “planned in a logical and systematic manner.” Another was to consider consolidation with adjoining cities.

Another problem, however, was stated to be that “the environment for residence and commerce may perhaps be less than desirable” because “bars and similar facilities” might be attracted which “may tend to degrade property . . . and to attract undesirable persons.” Additionally, there was concern about coherence and community life. The answere here was to pay more attention to planning and urban renewal, though the question of what could be permitted is an interesting one relating to zoning and legal issues. Having some residential areas as well as “community cultural and recreational programs” was identified.

Also cited as an issue was how to make an industrial city a desirable one in terms of its housing and it was noted that attractive housing and community amenities were important. So was having “well-qualified professional persons to staff governmental and community agencies.” Having business owners who lived outside the city appointed to commissions and committees was also mentioned with respect to perceived conflict between these business owners and residents.

With respect to planning with neighboring cities and communities in the region, because “the city is an integral part of the region,” it was recommended that “informal cooperative relationships” be created to assist with planning, locally and regionally. It was also suggested that “the city may develop buffer zones of commercial development so as to separate the industrial areas of the city from residential areas in neighboring cities.”

Taxation was also cited as a potential problem in that “tax-base fragmentation” could arise and lead “to imposition of regional planning and tax-base sharing to the detriment of local autonomy and finance.” The idea here was to collaborate with local and regional communities, though the newly created Local Agency Formation Commission was considered a first step in state action for planning changes. Along the line of taxation, it was suggested to divert income tax monies from special-purpose cities and the response was to convince others that this was “actually directed at the very concept of local government.”

A notable issue was that “the industrial city needs to convince surrounding cities specifically . . . of the necessity, if not the desirability, of incorporating special-purpose cities,” because “there is strength in unity” and this would be accomplished “through conferences, through support of local government in general, and through participation in various plans and programs of other local jurisdictions.”

Finally, the last identified potential problem was that “school districts may seek to condemn [undeveloped] land for new school sites,” especially parcels in an industrial city adjacent to growing residential areas. It was asserted that districts preferred developing on open land, even though they didn’t normally build facilities in industrial areas. Building schools in these locations “raises problems relating to traffic control, policing, and numerous other matters.” The answer was to “maintain good cooperative planning relationships with the school districts” because “there is no defense against condemnation proceedings by a public agency.”

Turning to the reasons for businesses to locate in the City of Industry, the Institute sent questionnaires to companies in the city, basing these on other “plant-location studies.” Ninety firms sent replies that were tabulated on a weighted basis. Addressing concerns of bias in the ordering of questions, the authors also noted that “the greatest weaknesses of the survey are the smallness of the sample and the possibility that too much significance will be attached to the apparent results.”

Among the respondents were fabricated metal product, chemical, electrical machinery, transportation equipment, furniture and fixture, and stone, clay and glass firms, while a dozen companies were in the wholesale business. There were, however, about a third of the respondents which reflected a diverse array of enterprises not reflected above.

The most important reason, with a weighted response of 14.33% was “proximity to markets for your products and/or services,” while not far behind, at 12.36%, was “availability of needed land acreage.” Running third, at 10.74% was “low land costs.” Answers about 5% included access to freeways and truck routes; proximity to “executive-level” residential communities; accesss to labor; proximity to railroad lines; and access to readily available utilities. Notably, low taxes and labor costs rated at 2.66% and 1.33%, respectively, while “favorable industrial climate” came in at 2.73% and compatible zoning, deed restrictions and easements was at 4.82%.

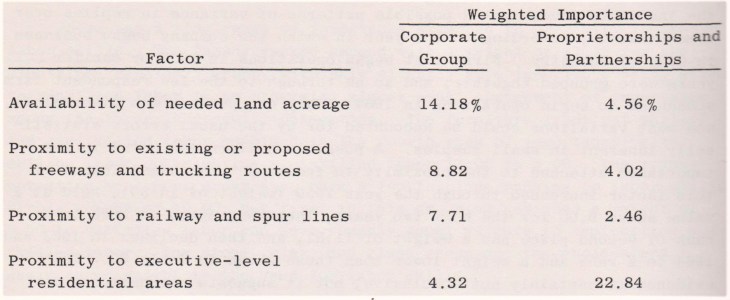

There were some variations in importance dependent on the type of industry as well as its legal structure (a larger corporation versus a smaller independent proprietorship and partnership, for example.) The larger firms, however, tended to identify land size and access to transportation as more important, while the latter much more preferred proximity to executive housing. It was noted that one variable that seemed to show a consistent pattern across the general categories of company was access to freeways, interesting given that the heyday of freeway construction was coming to a close at about the time of the study’s date range, that is, 1970.

Asking respondents about advantages and disadvantages of operating in the city, the authors reported that what was considered important prior to locating could change once firms were established in Industry. Companies were asked to provide five examples of each with an emphasis on the effect on the firm, not the totality of businesses in the city. Again, the responses were weighted for the 23 items listed.

The top advantage was proximity to markets, at a little over 10%, with low land costs, the city’s attitude towards indstry, labor availability and suitable housing availability the next four highest at between 8% and 9.5%. Rounding out the top ten, between 6.3% and 4% were desirable lot sizes; zoning and operating requirements; freeway, highway and trucking access; general transportation and distribution; and adequate supplies of utilities. Low taxes finished in the middle of the pack, with location and cost of labor at 17th and 18th.

Proximity to markets, though, was closely related to proximity of markets and suppliers and proximity to suppliers, the latter of which together constituted about 6% of the responses, putting a combined total at a little over 16%. It was also observed that separating freeways and highways from general transportation, rail transportation, and shipping costs, local traffic and miscellaneous transportation made little sense. Together, those four totaled nearly 13.5% of the replies. Several labor questions pooled together also came to about 13.5%.

Disadvantages were far fewer in number (173 total compared to 332 advantages) and it was stated that this “would appear to be a vague but somehow meaningful expression of general satisfaction” with the city. Highest, at 16.6% was local traffic conditions, with lack of restaurants second at 10.6%. Issues with telephone service were the third and fourth largest issues and combined totaled 16.4%. Taxes came in fifth at a little below 5%. Eight items tallied between 3 and 4%, including labor, distance from markets, flood control, shipping costs, and others. Interestingly, smog was 15th at 2.4%.

Comparing the two categories, the authors noted that “labor must be considered a strong favorable factor” in that the responses to access to good labor pools were generally positive. The lack of restaurants was highlighted. Transportation was, not surprisngly, complex, with access to routes generally seen as advantages, while traffic west into Los Angeles and in two specific areas of the city (near rail crossings and in an older area of town near Valey Boulevard and Puente Avenue) was an impediment. Proximity to markets and availability to suppliers also came out well, while perceptions of regional growth was noted as an advantage by a number of firms.

The availability and cost of land were also highly favorable to firms, not surprising given the city’s development by 1964 and, generally, those questions related to the city’s attitude toward business, the industrial climate or the responsiveness of local government brought largely complimentary responses.

Finally, there was a separate survey sent to 75 realtors speciailizing in industrial properties and asking only for unfavorable conditions. There were 22 responses, with the poor appearance of the city coming in highest at 17.75%, followed by poor freeway access at 14.19% and poor accessibility from other areas at 11.83%. The other three responses above 5% were climate (including smog), telephone rates, and poor labor availability.

Asked to supply steps that could be taken to improve conditions, the realtors offered fourteen suggestions. The major ones were:

- improving the road system, including grade crossings

- improving drains and sewers

- keeping taxes low

- consolidating water companies

- enhancing zoning to “eliminate haphazard industrial development”

- improving building standards

Others were mentioned just once and included keeping the city’s governing costs low, improving freeway access, developing a master plan, establishing a “businessman’s liaison committee” to work with city officials, and getting more stores and shops.

The reason for going into such detail with this report is because it marked the first attempt to systematically look into the City of Industry as a place to do business, just seven years following incorporation. More than a half century later, the report can be compared and contrasted not only to what has transpired since its issuance in June 1964, but to what the future holds for the city.